Caché MapReduce - introduction to BigData and MapReduce concept

Several years ago everyone got mad about BigData – nobody knew when smallish data will become BIGDATA, but all knows that it’s trendy and the way to go. Time passed, BigData is not a buzz anymore (most of us missed the moment when Gartner has removed BigData term from their 2016 buzzword 2016 curve http://www.kdnuggets.com/2015/08/gartner-2015-hype-cycle-big-data-is-out-machine-learning-is-in.html), so it’s probably a good time to look back and realize what it is (what it was)…

When it becomes “BigData”?

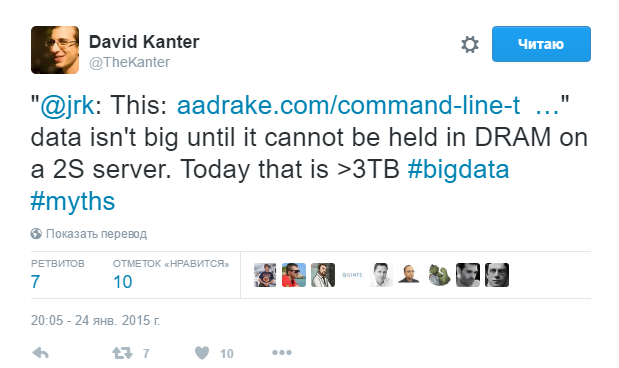

Let’s start from the beginning: what is the moment when “not so big data” becomes BigData? Here was the answer in 2015 from David Kanter[1], one of most respected, well known x86 architecture specialists

https://twitter.com/thekanter/status/559034352474914816

So if you have “only a couple” of terabytes data then you probably could find an appropriate hardware configuration which will held it entirely in memory, [well, given enough of motivation and budget], so it’s probably not yet “the BigData”.

BIGDATA starts from the moment when vertical upscale approaches (finding bigger hardware) stop to work because there is no bigger hardware (which still is reasonably expensive) available at the moment, so you need to start to think rather horizontally, and not vertically.

Simple the better - MapReduce

Ok, now we know volume size which would be threshold for BigData approach, then we need to figure out appropriate approach which we will use for handling such big volume. One of the first approaches started to be used with BigData was (and still is) the MapReduce programming model. There are multiple known programming models for big data which are probably simpler and may be more flexible than MapReduce, but MapReduce is definitely the most simplistic, well known, but not necessary the most efficient one.

And, if one talks about some database platform as supporting BigData, he, most probably, means that platforms does support some MapReduce scenario using some built-in or external interfaces and infrastructure.

Putting it the other way: if there is no MapReduce – you could not claim BigData support in the platform!

If you were outside of internet last 10 years and missed MapReduce then we will try to explain it in details quite soon, but for now please remember that MapReduce is a generic paradigm to get wide scalability effect using very simple (albeit not very much efficient) instruments.

It's frequently observed that simplest approach allows to get better results, and, most probably, using least expensive way. Even being not the most efficient way, it will be used longer, and will have better chances to get widespread usage with easier learning curve.

This effect has happened with MapReduce model, while being very simple one, it’s got widely used in many areas, where original authors could not even anticipate it at the beginning.

Caché specific scalability approaches

Historically, InterSystems Caché has many well established tools for both vertical and horizontal scalability: as we know it's not only the database server, but also is the application server, which uses ECP protocol for scalability and high-availability.

The problem with ECP protocol – while being very much optimized for coherent parallel execution on many nodes, it still very dependent on the write daemon performance of a single node (central database server). ECP capabilities help you when you need to add extra CPU cores with the modest write-daemon activity, but not will help you to scale horizontally the write activity, because the database server will still be the bottleneck.

Modern BigData applications implicitly assume the different or rather opposite approach – to scale performance horizontally using each particular node write capabilities. In reverse to ECP approach, when data is brought to application on several nodes, we rather assume that application size is thin/”reasonable” but data amount is enormous, so we better to bring code to the local data, and not the opposite. This sort of partitioning is named “sharding” and will be addressed in Caché SQL engine in general with some future InterSystems Caché solutions, but in a mean-time we could try to use some simpler, but already available means, using that we have today.

Although, I’m not big fan of original BigData approach (see Mike Stonebraker articles “Possible Hadoop Trajectories”, “Hadoop at a crossroads?”, [Russian translation is here ]), and it’s not a panacea of any sorts, but MapReduce still may be a good start for future developments, so let us get whatever we have in the Caché as development platform, and implement some simplified MapReduce which may be still helpful for developers right away.

Google MapReduce

The original Google MapReduce implementation was in C++, but coincidentally, the wide usage in the industry MapReduce achieved only thanks Apache Hadoop implementation which was in the different language - Java. In any case, regardless of a particular implementation language, the idea is more or less the same, be it C++, Java, Go, or, in our case, Caché ObjectScript. [Though for ObjectScript case we will use a few shortcuts, which are possible thanks to hierarchical arrays capabilities also known as globals].

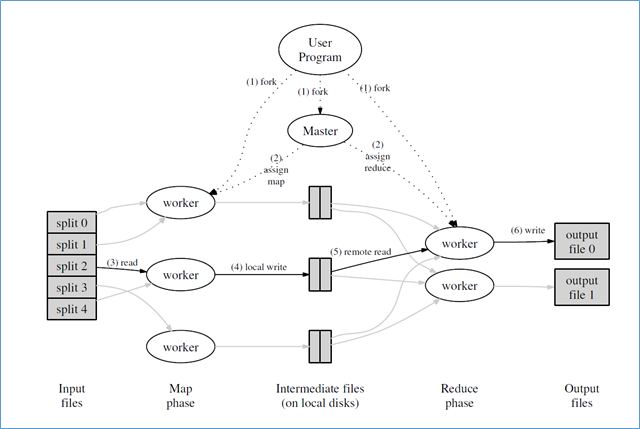

Figure: MapReduce Execution Overview from "MapReduce: Simplified Data Processing on Large Clusters", OSDI-2004

Here is the simplistic MapReduce algorithm depicted in the picture above:

- We have a bunch of input files or, potentially infinite, data stream, which we could somehow partition to the number of independent chunks;

- Also we have some number of parallel workers (local to the current node or probably remote) which will be assigned to some input chunks (this is called “map phase”);

- Those workers proceed input data stream(s) and then emit output data in a simple key-value form to the output stream(s).The output stream written to simple files or anywhere else (i.e. to cluster wide filesystem, like Google GFS or Apache HDFS, based on some external magic).

- At the next stage, “reduce phase“, we have another set of workers, which do their “reduction” work. They read value collections for some given key, and provide resultant key-value written to the output files (which are still residing on some magical cluster file-systems).

- MapReduce approach is batch by their nature. It’s unable to handle true infinite input-streams and will wait completion of each stage (map or reduce) before going to the next pipeline. This is difference with more modern “streaming” approaches used in Apache Kafka, which could handle in parallel infinite input streams.

Is it clear? Probably, not yet. Let me try to clarify it using classical word-count example, given in the original Google’ article.

Consider a case when we need to count the number of unique words in the collection of files.

I’m C++ developer in my background, so any algorithm became crystal clear once we see true C++ example. On the other hand, if you have no prior C++ knowledge then bear with me, I’ll try to explain it later, using simplified algorithmic language.

#include "mapreduce/mapreduce.h"

// User's map function

class WordCounter : public Mapper {

public:

virtual void Map(const MapInput& input) {

const string& text = input.value();

const int n = text.size();

for (int i = 0; i < n; ) {

// Skip past leading whitespace

while ((i < n) && isspace(text[i]))

i++;

// Find word end

int start = i;

while ((i < n) && !isspace(text[i]))

i++;

if (start < i)

Emit(text.substr(start,i-start),"1");

}

}

};

REGISTER_MAPPER(WordCounter);

// User's reduce function

class Adder : public Reducer {

virtual void Reduce(ReduceInput* input) {

// Iterate over all entries with the

// same key and add the values

int64 value = 0;

while (!input->done()) {

value += StringToInt(input->value());

input->NextValue();

}

// Emit sum for input->key()

Emit(IntToString(value));

}

};

REGISTER_REDUCER(Adder);

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

ParseCommandLineFlags(argc, argv);

MapReduceSpecification spec;

// Store list of input files into "spec"

for (int i = 1; i < argc; i++) {

MapReduceInput* input = spec.add_input();

input->set_format("text");

input->set_filepattern(argv[i]);

input->set_mapper_class("WordCounter");

}

// Specify the output files:

// /gfs/test/freq-00000-of-00100

// /gfs/test/freq-00001-of-00100

// ...

MapReduceOutput* out = spec.output();

out->set_filebase("/gfs/test/freq");

out->set_num_tasks(100);

out->set_format("text");

out->set_reducer_class("Adder");

// Optional: do partial sums within map

// tasks to save network bandwidth

out->set_combiner_class("Adder");

// Tuning parameters: use at most 2000

// machines and 100 MB of memory per task

spec.set_machines(2000);

spec.set_map_megabytes(100);

spec.set_reduce_megabytes(100);

// Now run it

MapReduceResult result;

if (!MapReduce(spec, &result)) abort();

// Done: 'result' structure contains info

// about counters, time taken, number of

// machines used, etc.

return 0;

}- The program is invoked with the list of files it should process (passed in standard argc/argv);

- MapReduceInput object instantiate with each input argument, and scheduled to run mapper class (WordCounter) for each input;

- MapReduceOutput is instantiated to output data to some “magical” Google cluster filesystem (e.g. /gfs/test/*);

- Reducer and combiner classes assigned to C++ class Adder, implemented in this same program;

- Function Map in Mapper class (implemented by WordCounter class in our case) receives input data via generic MapInput interface. In this case it will be file reading interface. It gets content of this data source via value() function, and length of the data source via size() function;

- For the purposes of the original exercise it should ignore all whitespaces (isspace(x)), and count anything between white-spaces as a word. The word found is then written to output stream via Emit(word, “1”) function;

- Function Reduce, in the Reducer class (implemented by Adder class), receives reducer input data via generic ReduceInput interface. This function called for some particular key value (found word in the mapper stage) with the collection of all values sent for this key from mapper (sequence of 1 in our case). The responsibility of a reducer function is to count these 1s and emit their sum to the output channel.

- This was responsibility of a MapReduce master to prepare such input collection of values for the given key. Details of particular implementation will heavily dependent of a protocol used in the cluster, so we will leave it outside of this story. In our case, for the Caché ObjectScript implementation it will be quite easy, thanks to sorted nature of globals.

- There are cases when one or more extra reduce step(s) will be required (i.e. if 1st reduce step didn’t process whole input data set), then there is Combiner step(s) used, which will aggregate the data collected by prior (1st) reduce step. Depending on circumstances and algorithm used, you may need to use multiple combiner steps for aggregation of generated data.

Is it clear already? No? Ok, here is simplified description of the algorithm Google MapReduce implementation (which is looking like Python, but is not actual Python):

map(String key, String value): // key: document name // value: document contents for each word w in value: EmitIntermediate(w, "1"); reduce(String key, Iterator values): // key: a word // values: a list of counts int result = 0; for each v in values: result += ParseInt(v); Emit(AsString(result));

Responsibility of a map function to generate list of <key,value> pairs. Those pairs shuffled and sorted elsewhere, on the controller nodes, and sent to reducer I consolidated collections for each separate key. Responsibility of reduce function – get collection of values for the given key, and generate the output key-value pair or list of such pairs. (The number of words for our case)

In the classical MapReduce implementation transformation of a collection of <key, value> to the separate collections of <key, <value(s)>> is most time consuming operation. However, it will not be a such big deal in our Caché implementation, because b-tree* -based storage will do all the ground work for us, if we use global as our intermediate storage. More details later.

This is probably enough for the introduction part – we have not provided anything ObjectScript related, but have provide enough of details of MapReduce algorithm for which the corresponding ObjectScript implementation will be shown in the later parts of this series. Stay tuned.

Comments

Interesting to see this talk being advertised today:

https://jaxlondon.com/session/no-one-at-google-uses-mapreduce-anymore-c…

The world has moved on, it seems.

There is Russian proverb for such cases "Rumors about my death is slightly exaggerated"[1] . Be it BigData, which is declared by Gartner as dead, but is here to stay, in slightly wider form and in more scenarios, or be it MapReduce. Yes, Google marketers claim to not use it anymore, after they have moved to better/more suitable for search interfaces, and yes, in Java world Apache Hadoop is not the best MapReduce implementation nowadays, where Apache Spark is the better/more modern implementation of the same/similar concepts.

But life is more complicated than that shown to us by marketing, there are still some big players, which are still using their own C++ implementation of MapReduce in their search infrastructure - like Russian Yandex search giant. And this is big enough for me to still count it as relevant.

[1] As Eduard has pointed out that was Mark Twain who originally said "The report of my death was an exaggeration." Thanks for correction, @Eduard!