AI Agents from Scratch Part 3: The Pulse of the Machine

Welcome to the finale of our journey in building MAIS.

- In Part 1, we constructed the agnostic "Brain" using LiteLLM and IRIS.

- In Part 2, we designed the "Persona", mastering Dynamic Prompt Engineering and the ReAct theory.

Now, the stage is set. Our agents are ready, defined, and eager to work. However, they remain frozen in time. They require a mechanism to drive the conversation, execute their requested tools, and pass the baton to one another.

Today, we will assemble the Nervous System. We are going to implement the Orchestrator using InterSystems BPL, creating a living, breathing loop that transforms static definitions into a functional Multi-Agent setup.

Let’s enter the Bistro and turn on the lights.

The Challenge

To make this "Thinking Loop" functional, our LLM Adapter must send tool definitions to the provider. This is where development deviates from a linear path and encounters an obstacle.

Here is the context: litellm (like the OpenAI SDK) relies heavily on Python's Keyword Arguments (**kwargs). To make a standard request, you pass a model and messages. However, if you wish the agent to employ tools, you must optionally hand over tools and tool_choice.

Mapping this dynamically from ObjectScript to Python turned out to be messy.

- If we pass

toolsas an empty list[]when no tools are needed, some providers throw validation errors or start hallucinating function calls. - If we try to hand over

nil, the Python gateway might interpret it incorrectly. - Obviously, we needed a robust way to construct the arguments dictionary dynamically before calling the library.

The Solution: A Python Wrapper Method

Instead of fighting the interoperability layer with complex ObjectScript logic, I decided to embrace it. I refactored the Adapter to include a helper method written directly in Python ([ Language = python ]).

This method, PyCompletion, acts as a bridge. It receives complex data (Messages and Tools) as JSON Strings, which are trivial to generate in IRIS, and handles the dictionary unpacking inside the Python environment.

It solved three problems simultaneously:

Serialization: We handle JSON parsing within Python, securing native types (dicts and lists).

Conditional Logic: We check if toolsJson exists. If not, we simply omit the "tools" key to the kwargs dictionary.

Cleanliness: The ObjectScript code remains clean, focusing on logic, while the Python code handles the library specifics.

Below you can see the refactored method that saved the day:

ClassMethod PyCompletion(model As %String, messagesJson As %String, toolsJson As %String) As %SYS.Python [ Language = python ]

{

import litellm

import json

# 1. Parse the JSON strings coming from IRIS

msgs = json.loads(messagesJson)

# 2. Build the arguments dictionary

kwargs = { "model": model, "messages": msgs }

# 3. Conditionally add tools

# This prevents sending empty lists or nulls to providers that don't support them

if toolsJson and toolsJson.strip() != "":

kwargs["tools"] = json.loads(toolsJson)

kwargs["tool_choice"] = "auto"

# 4. Call LiteLLM unpacking the dictionary

return litellm.completion(**kwargs)

}

Now, calling the LLM from our Adapter is as simple as the following line:

Set tResponse = ..PyCompletion(tModel, tMessages.%ToJSON(), tTools)

This piece of code is concise, but it ensured our architecture remains robust regardless of whether the agent needs to call a complex function or just chat about the weather.

Closing the Loop: The Mechanics of Tool Execution

Now, as we have the tools and the handoff logic, we need to make the Orchestrator actually run them.

If the LLM decides to utilize a tool, it does not return plain text for the user. It returns a Tool Call Request. Iit means our Orchestrator cannot simply be a linear "Input -> Process -> Output" line. It must be a Loop.

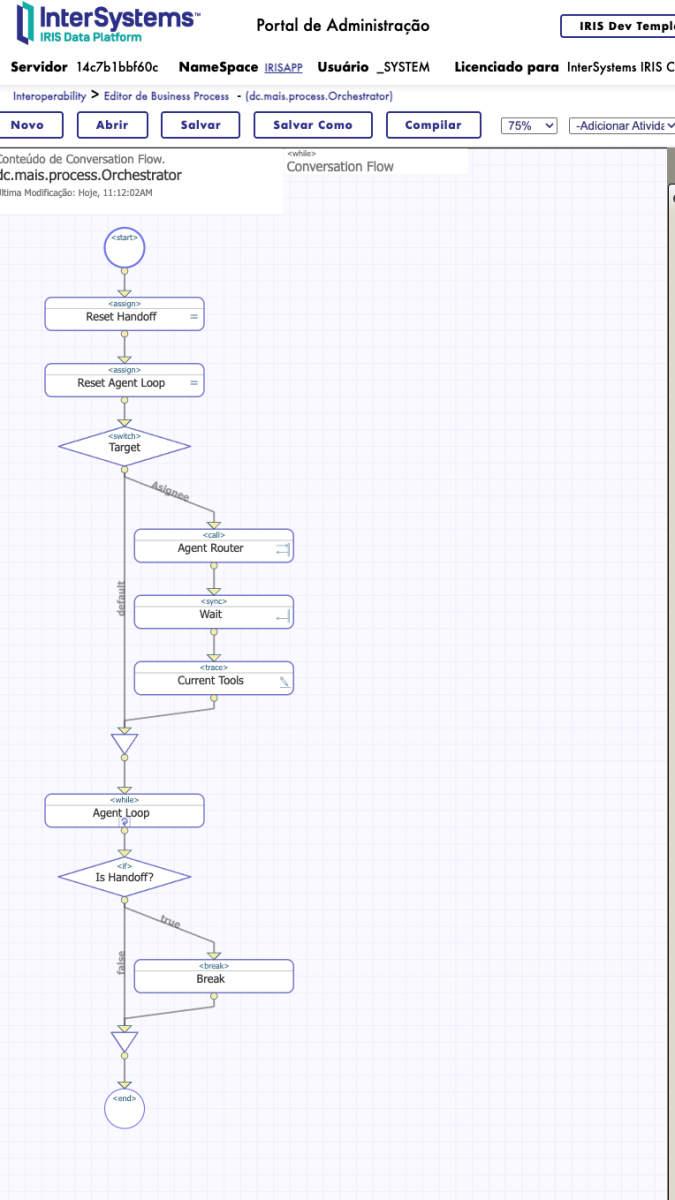

I modified the Orchestrator BPL to include a While loop named AgentLoop, controlled by a context variable RunLoop. The logic is simple: keep the agent active as long as it is "thinking" or "working."

If the LLM returns a ToolCall, it means the Intelligence has requested an action. We must execute it, and this is crucial return the result to the LLM so it can formulate a final answer.

The Parsing Challenge

This process is trickier than it appears. Here is where it gets fiddly. We have to parse the JSON response to identify which tool is being called and which parameters should be shipped with it.

Before calling the AI, I added a <code> block named Prep AI Call. Its job is to manage the conversation focus. If we are returning from a tool execution, we should clear the UserContent, since the AI needs to focus on the tool's result, rather than reprocess the user's original question.

// If returning from a Tool execution, clear User Input to shift focus to tool result

If (context.CurrentToolId '= "") {

Set context.userContent = ""

}

After the AI responds, we check whether context.ToolCall is empty. If it has data, we enter the parsing phase.

Honest Note: In BPL, handling complex dynamic objects can sometimes be verbose with standard shapes. I often use <code> blocks for this type of logic since it allows me to write standard ObjectScript, which I find more readable for JSON manipulation.

Below, I mentioned the Parse Tool Call logic. It extracts the function name and ID. Yet, crucially, it updates the conversation history to record that the Assistant attempted to call a tool.

Set context.CurrentToolName = ""

Set context.CurrentToolId = ""

If ($Length(context.ToolCall) > 5) {

Try {

Set tArray = [].%FromJSON(context.ToolCall)

Set tItem = tArray.%Get(0)

If $IsObject(tItem) {

Set context.CurrentToolName = tItem.function.name

Set context.CurrentToolId = tItem.id

// Update History with the REQUEST (The Assistant's intent)

Set tHistArray = [].%FromJSON(context.History)

If (tHistArray = "") Set tHistArray = []

Set tMsg = {}

Set tMsg.role = "assistant"

Set tMsg.content = context.CurrentResponse

Set tMsg."tool_calls" = tArray

Do tHistArray.%Push(tMsg)

Set context.History = tHistArray.%ToJSON()

}

} Catch e {

$$$LOGERROR("Parse error: " _ e.DisplayString())

}

}

The Protocol: Why tool_call_id Matters

You might be wondering: "Why do we need this ID?"

When such models as OpenAI, Claude, or Gemini decide to use a tool, they generate a transaction ID.

{

"role": "assistant",

"tool_calls": [

{

"id": "call_12345",

"function": { "name": "get_menu", "arguments": "{}" }

}

]

}

When we send the result back (e.g., the menu items), we must tag that message with the same ID. This is how the model connects the dots: "Ah, this JSON data is the result of that get_menu request I made two seconds ago."

To close this loop, I updated the LLM Adapter to handle the response injection:

// Inject Tool Output if present (Close the Loop logic)

If (pRequest.ToolCallId '= "") && (pRequest.ToolOutput '= "") {

Set tToolMsg = {}

Set tToolMsg.role = "tool" // Special role for tool outputs

Set tToolMsg.content = pRequest.ToolOutput

Set tToolMsg."tool_call_id" = pRequest.ToolCallId

Do jsonHistory.%Push(tToolMsg)

}

A Note on Model Compatibility

It brings up an important question: Can any LLM do this?

In theory, yes. Any LLM (even a local SLM running on a laptop) can be prompted to follow a convention similar to "When you want to use a tool, write CALL:get_menu {}", and you could then parse that text with Regex.

However, it is fragile since the model might hallucinate the format or forget the brackets.

For this project, I used GPT-5 (or modern variants like GPT-4o/Claude 3.5). These models are fine-tuned with specific examples of instruction + tools → valid tool_calls. They effectively speak "JSON Protocol", since it is native to them. While you can still build agents with smaller models, using a model trained for Function Calling makes the architecture significantly more robust and the parsing code much cleaner.

The Relay Race: Mastering the Handoff

We have established how to send tools to the brain. However, we are overlooking the most vital tool in the box. In this architecture, the most critical action is not running a query; but knowing your limits.

Once the MenuExpert locks in that Coq au Vin, it needs to stay within its lane. It does not have the clearance to process payments and should signal the OrderTaker.

Auto-Injecting the Handoff Tool

I modified the dc.mais.adapter.Agent class to include a method called GetComputedTools(). This method does a simple merge: it takes the specific tools you defined (e.g., get_menu) and appends a mandatory, hardcoded tool named handoff_to_agent.

This tool requires two arguments:

target_agent: Who are we sending the user to?reason: Why are we transferring them? (Crucial for context).

Here is the trick:

Method GetComputedTools() As %String

{

// 1. Define the Standard Handoff Tool

Set tHandoff = {

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": "handoff_to_agent",

"description": "Transfer the conversation to another agent when the current goal is met or scope is exceeded.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"target_agent": { "type": "string" },

"reason": { "type": "string" }

},

"required": ["target_agent", "reason"]

}

}

}

// 2. Merge with User Tools

Set tTools = [].%FromJSON(..Tools)

Do tTools.%Push(tHandoff)

Return tTools.%ToJSON()

}

Now, every agent in our system automatically knows how to delegate tasks.

The Fork in the Road: Executing the Logic

It is time for us to go back to our Orchestrator BPL. It is where the rubber meets the road.

When we call the LLM, it returns a response. That response might be plain text ("Hello!") or it a structured request to run a function.

We need to trap this. Inside our BPL loop, we check the following: Did the LLM return a Tool Call?

If yes, we face a fork in the road:

- Is it a Business Tool (e.g.,

get_menu)? If so, we invoke the genericToolRunner, which executes the SQL query and returns the JSON. - Is it the

handoff_to_agentTool? It is a special one. We do not call an external service, but instead, we change the internal state of our process.

In the BPL, I implemented a specific case for this:

<case condition='context.CurrentToolName="handoff_to_agent"'>

<code name='Process Handoff'>

<![CDATA[

// 1. Extract arguments

Set tArgs = {}.%FromJSON(context.ToolCall).%Get(0).function.arguments

Set tNewTarget = {}.%FromJSON(tArgs)."target_agent"

// 2. The Magic: Change the Orchestrator's Target

Set context.Assignee = tNewTarget

// 3. Reset loops to wake up the new agent

Set context.IsHandoff = 1

Set context.RunLoop = 0

]]>

</code>

</case>

This is the power of BPL. We treat a "Tool Call" not just as an API request, but as a Control Flow Signal.

When the MenuExpert calls handoff_to_agent("OrderTaker"), the BPL breaks the current loop, updates the Assignee variable, and immediately starts the loop for the OrderTaker. To the user, it feels seamless: one moment they are discussing wine, and the next, someone is confirming their billing details.

The Heartbeat: The Double Loop Architecture

So, the MenuExpert decided to hand off the conversation. It called the tool, we caught it and updated the context.Assignee variable to "OrderTaker".

Mission accomplished, right? Wrong.

If our BPL were a simple linear sequence, the process would reach the end of the diagram and terminate right there. The OrderTaker would never get a chance to speak because the process would simply be finished.

To make this a living, breathing conversation, we need a Heartbeat. We require an architecture that I call the Double Loop.

1. The Inner Loop (The Thought Process)

We have already built this. It is the AgentLoop we discussed earlier. It handles the ReAct cycle: Think -> Tool -> Think -> Answer. This loop runs as long as the current agent has work to do.

2. The Outer Loop (The Stage Manager)

This is a new piece of the puzzle. We should wrap the entire logic inside a massive While loop named "Conversation Flow".

Think of this outer loop as the Stage Manager. Its only job is to ask: "Who is supposed to be on stage right now?"

See below how the flow works in the BPL:

- Start Outer Loop: The process wakes up.

- Reset Flags: We set

context.IsHandoff = 0. We assume the current agent will finish the job unless told otherwise. - The Switch: We look at

context.Assignee.

- Is it

"greeter"? -> Load Greeter's Prompt. - Is it

"order_taker"? -> Load OrderTaker's Prompt.

- Run Inner Loop: The chosen agent does its ReAct magic.

- Check Handoff:

- If the agent finishes normally (responds to the user), the inner loop ends, and we pause for user input.

- BUT, if the agent calls

handoff_to_agent, we break the inner loop immediately.

Since we are inside the Outer Loop, the process does not just die, but loops back to the top. It resets the flags, hits the Switchagain, sees that Assignee has changed to "OrderTaker", and instantly loads the new persona.

To the user, all of that is invisible. They only see the Greeter say "Let me get someone to help you," and a split second later, the MenuExpert chimes in with "Bonjour! How can I help you navigate our menu?"

This Double Loop is what separates a script from a system. It allows the conversation to bounce between 2, 5, or 50 agents indefinitely, maintaining the context history at all times. It is the engine that keeps the bistro running.

The Golden Thread

At this point, we have a Brain (LLM), Hands (Tools), and a Heartbeat (Double Loop). However, we have only scratched the surface of Memory.

If the Greeter hands off the conversation to the MenuExpert, the new agent will need to know what happened before. If I tell the Greeter, "I am allergic to peanuts," but the MenuExpert suggests a Peanut Satay, the system has failed, no matter how smart our routing is.

I call this persistent context "The Golden Thread."

In our BPL, the context.History variable acts as this thread. It is a JSON array that captures every interaction:

User: "Do you have vegan options?"

Assistant (Greeter): "Let me ask our specialist."

System (Handoff): "Transferred to MenuExpert."

User: (Silence/Waiting)

Assistant (MenuExpert): "Hi! Yes, we have a Ratatouille..."

By passing this History object intact from one loop iteration to another, the MenuExpert wakes up with the full context of the conversation already loaded in its short-term memory. It knows precisely why it was called.

To make this work nicely, let's add a property called History to our message. Then, in the Business Process, we should insert a <code>block named Initialize History to handle the incoming context:

// 1. Load the Request's History

Set context.History = request.History

If (context.History = "") { Set context.History = "[]" }

// 2. Add the Current User Input to the History IMMEDIATELY

// This ensures the LLM sees the complete context and the input appears in the final response

If (context.userContent '= "") {

Set tHist = [].%FromJSON(context.History)

Set tUserMsg = {}

Set tUserMsg.role = "user"

Set tUserMsg.content = context.userContent

Do tHist.%Push(tUserMsg)

Set context.History = tHist.%ToJSON()

// 3. Clear userContent to avoid duplication

// Since it's already added to the History, there's no need to send it separately to the LLM Adapter

Set context.userContent = ""

}

Nice! There is still one loose end to tie up. The memory logic also needs to account for the moments when the AI chooses not to use a tool (basically, whenever it only sends a standard text reply).

Inside the loop, after the AI call, let's add another <code> block named Update History:

If (context.CurrentResponse '= "") {

// 1. Load the existing history

Set tHistArray = [].%FromJSON(context.History)

If (tHistArray = "") Set tHistArray = []

// 2. Create the assistant's final message

Set tMsg = {}

Set tMsg.role = "assistant"

Set tMsg.content = context.CurrentResponse

// 3. Add to the array and save in context

Do tHistArray.%Push(tMsg)

Set context.History = tHistArray.%ToJSON()

}

Elevating from "Demo" to "Micro Framework"

Alright then. The Orchestrator I described above was hardcoded for our Bistro and had specific Switch cases for Greeter and MenuExpert. It is fine for understanding the role of an orchestrator, but it is not a Framework. If I wanted to build a Tech Support bot next, I would have to rewrite the BPL entirely.

To fix that, I refactored the architecture to be truly agnostic. I moved the core logic into a generic component: dc.mais.engine.Orchestrator.

This engine does not know who the agents are. It does not care if you are running a Bistro or a Bank. Instead of hardcoding the routing logic, it simply delegates that decision to Plug-and-Play Business Processes.

I implemented what is essentially a Strategy Pattern using BPLs:

- The Engine (

dc.mais): Handles the Double Loop, Memory, and LLM calls. It is essentially a "Black Box." - The Router (

dc.samples): You create a simple BPL (e.g.,AgentRouter) that contains only a Switch statement mapping names, e.g., "sales" toAgent.Sales. - The Runner (

dc.samples): You design a BPL (e.g.,ToolRunner) that maps function names. e.g., "get_balance" to the actualTool.GetBalanceoperation.

Amazing job! We have successfully separated the Mechanism (How to run an agentic workflow) from the Policy (Which agents exist and what they do).

Now, you can install dc-mais as a library and build your own team of agents without ever touching the core engine code.

X-Ray Vision and the Full Crew

So, where do we stand?

We started with just an idea, but ended up with a brain. We built an Adapter that connects to any LLM provider supported by LiteLLM (Azure, OpenAI, Bedrock, you name it). We defined a Persona structure with roles, goals, and tasks. We architected a Conductor using the Dual Loop to master the ReAct Paradigm:

- Get the Mission: A goal comes in (e.g., "I want a burger").

- Scan the Scene: The agent gathers context from history.

- Think It Through: The brain formulates a plan.

- Take Action: The orchestration layer executes a specific tool.

- Observe and Iterate: The agent sees the result and decides on the next move.

And we didn't stop there. Our Orchestrator handles tools and explicit Handoffs, allowing specialized agents to pass the baton smoothly. This modular design means we aren't trying to build one "God Mode" prompt; we are building a team of experts.

In other words, dc-mais has evolved into a full-stack agentic platform comprising the following:

- Reasoning Engines: The LLMs that understand the tasks.

- APIs & Tools: The hands connect to the real world.

- Orchestration Layer: The BPL that plans and assigns work.

- Multi-Agent Network: The specialized team handles the workflow.

The Visual Trace

There is one massive advantage we have not touched yet, and it is the main reason why I chose InterSystems IRIS: Visual Tracing.

Debugging asynchronous AI agents in pure Python can be a nightmare of log files and print statements, but in IRIS, we get X-Ray vision.

[Caption: Look at how clean the message flow is between Agent.MenuExpert and Tool.GetMenu]

We can literally see the thought process. We observe the Orchestrator calling the Agent, the Agent deciding to use a tool, the Tool executing, and the result being fed back into the brain. It magically turns a "Black Box" into a transparent diagram.

Expanding the Bistro

To prove it works at scale, let's complete our demo by adding the final two members of our crew to the Production:

- Agent.OrderTaker: Think of this one as the digital waiter managing the check. It adds items, tracks quantities, and corrects mistakes using such functions as add_to_order or clear_order. When the user is satisfied with the selection, the agent triggers the handoff to the OrderSubmitter.

- Agent.OrderSubmitter: This agent finalizes the deal. It collects the table number (we can randomize it for now) and submits the ticket to the kitchen with

place_order, returning a confirmation ID and estimated time.

Finally, our flow looks like a real business process:

- Customer starts a chat → Greeter welcomes.

- Customer asks about food → Handoff to MenuExpert.

- Customer decides to eat → Handoff to OrderTaker.

- Order complete → Handoff to OrderSubmitter.

- Ticket sent to the kitchen → End of workflow.

Conclusion

Well, self-praise stinks, but we do have a pretty interesting micro-framework here! Isn’t it perfect? Far from it. Yet, it has potential (or might be just the ChatGPT flattery affecting my ego, lol).

We built a system that maintains state, respects business rules, and leverages the power of LLMs without losing control. InterSystems IRIS BPL provides the visual structure that Python scripts often lack in production.

If you wish to poke around the code yourself, the full project is up on GitHub and Open Exchange. My main goal here was to strip away the 'magic' and show you that the ReAct loop is actually pretty graspable. Feel free to reach out with feedback. I really want to see what you create with this framework.

Acknowledgments: A special shout-out to Fabio Silva, an Interoperability Wizard who gave me valuable tips on BPL.

Thanks for reading.